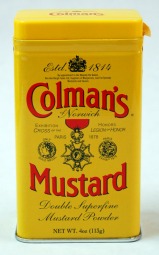

When we buy mustard in the store today, we don’t have to think about its preparation. However, mustard has a long history and has gone through many iterations as a condiment. It is traditionally prepared by grinding mustard seeds to create powder, which is then mixed with liquid. The Romans, who were the first to create this paste, used wine. Later versions of this condiment were made with such ingredients as water, beer, lemon juice, and vinegar. In early 19th century England, Jeremiah Colman perfected the technique of grinding mustard seeds into a powder without creating heat, which would expose the seed’s oils and in turn evaporate the flavor. He established Colman’s Mustard in 1814, and was made mustard-maker to Queen Victoria in 1866.[1] With the production of high-quality mustard powder for the kitchen came the need for containers to hold it, and so we arrive at this mustard tin from around the 1890s.

The most interesting aspect of this mustard tin, however, is not what would have been held in it, but the way it is decorated. On the front of the tin is written the word MUSTARD, though all but the last three letters have been worn away. Below the letters is a portrait of a woman. Dark, curly hair frames her face, and a flowing, white scarf covers part of her head. She wears a heavy gold necklace and earrings that hang with small gold discs. Her garment is bedazzled with more gold beads that echo her jewelry. She has heavy eyebrows and dark eyes that look off to the side at something unknown. Her mouth is pulled into a mysterious half-smile. This nonspecific woman of color is used as a marketing tool for a spicy condiment because she is vaguely exotic to white American eyes. This stereotyped representation of non-white “otherness” exemplifies a Western tendency to cast anything Eastern and unfamiliar as mysterious and dark.[2] In this portrait, she is not a real person the white viewer is supposed to relate to, merely a symbol of the exotic that signals the spice of the mustard.

The use of this imagery may be connected to the concurrent American political climate surrounding immigration. In the late 19th century, the United States saw the rise of nativism, a political movement created by “Native Americans,” or the descendants of the original thirteen colonies. Immigration was unfettered for much of early American history, but as the country began to fill and job competition rose, anti-immigration sentiment rose with it. Some of the nativists’ anxieties were targeted, at the Irish or the Germans or the Chinese. But the 1880s saw the rise of an across-the-board anti-immigration movement that culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924, which imposed strict quotas on newcomers.[3] This mustard tin commodifies an image of an exoticized “other” in a political climate hostile to non-white ethnic groups in order to market the spicy condiment contained within.

Miranda Pettengill, CGP ’16

[1] “The History of Mustard,” The Nibble, accessed October 28, 2015, http://www.thenibble.com/reviews/main/condiments/history-of-mustard.asp.

[2] Minjeong Kim and Angie Y. Chung, “Consuming Orientalism: Images of Asian/American Women in Multicultural Advertising,” Qualitative Sociology 28 (2005): 73.

[3] Roger Daniels, Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 265.